The inspirational influence of new or previously unencountered art and culture on another person can be profound--especially when the subject of that new encounter is him or herself an artist. Some encounters result in personal transformations that can be physical, emotional, mental, and/or spiritual in nature. Folklorists had been collecting recordings of unusual indigenous musics since the advent of sound recording but it was only with the deep contacts made during World War II with "primitive" and isolated third world cultures all over the planet that a science of ethnomusicology exploded. In the 1950s, with a burgeoning popular music scene fast rising in capitalistic countries, Western entrepreneurs in the music industry decided to take a chance to test the popular appeal of non-Western musics on the Western populations. It was, of course, helpful that many of these new artists of Indian, African, Caribbean, and Latin American origins had been immigrating to places like New York, London, and Paris, where record company R & D men could encounter them. Thus, we were exposed to musics of India by artists like Ali Akbar Khan and Ravi Shankar, to West African traditions from artists like Babatundi Olatunji, to Caribbean and Latin American sounds from Cubans Mongo Santamaria and Tito Puente, as well as a plethora of new dance styles in the form of songs mamba, cha-cha, bassa nova, salsa, Calypso, Reggae, and the many other unfamiliar styles and tempos. Jazz artists Dizzy Gillespie, John Coltrane, and Pharoah Sanders were some of the early artists to show the influence of these international sounds though pop artists like The Tokens and do-wap bands also made good on the new rhythms and sounds they were hearing.

Cross-cultural bridges can be formed by the immigration of one musician to another place or by the popularization or media attention to visiting musicians--as was the case with not only Shankar and Khan but also with South African Hugh Masekela, Nigerian native Babatunde Olatunji, and many Cubano musicians and groups (including Beny Moré, Mongo Santamaria, and Desi Arnaz) spreading the Rumba across the Caribbean before the country became with its Communist politics. In the Sixties, Terry Riley, Don Ellis, Simon and Garfunkle and even the Beatles and many, many others are examples of artists who expressed this kind of influence in their music.

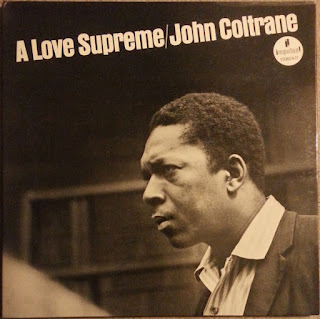

One cannot forget or overstate the influences of the "free jazz" movement in the 1950s. Jazz innovators such as Charles Mingus, Eric Dolphy, Albert Ayler, Archie Shepp, Joe Maneri, and Sun Ra pushed boundaries of popular music (remember, jazz was very popular at this time), while Ornette Coleman, Cecil Taylor, John Coltrane, Pharoah Sanders, and Sonny Sharrock were later carriers of the torch.

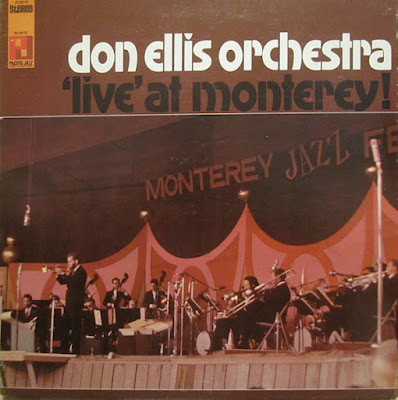

Spiritual and religious transformations can be another means to personal shifts in musical styles, forms and evolutions, as the Anglo-European world saw in the 1950s with the effect of the European and American tours of Ravi Shankar and Ali Akbar Kahn. The influences of Eastern philosophies, religions, culture, and music here are incredibly important with Ravi Shankar and Paramahansa Yogananda, Alan Watts, Sri Chimnoy, Maharishi Mahesh Yogi just a few of the names included in this list of world music disseminators; there would probably have never been a Don Ellis Orchestra, Santana's Caravanserai, or John McLaughlin's Mahavishnu music had these spiritual leaders not impregnated the Anglo-American consciousness.

John Coltrane had been a spiritual seeker ever since the "epiphany" that led to his break from his heroine and alcohol addictions in 1957. Though from a home in which both of his grandfathers were Christian ministers, and having found Islam through his first wife, Naima, in 1955, 'Trane was really a universalist and sought and believed there were truths to be found in all religions. Likewise developed his interest in world musics--all of which can be heard in his own musical expression and development over the last ten years of his life.

Then there is the trickle down effect: The Byrds' Roger McGuinn is reputed to have entered the recording sessions for the band's revolutionary song, "Eight Miles High" having listened repeatedly, for hours on end, to albums by Ravi Shankar and to John Coltrane's Impressions and Africa/Brass--in particular the song "India" from the former album. "It was our attempt to play jazz," claims McGuinn. Should one listen to the two songs ("Eight Mile High" and "India") back-to-back, one will find virtually the same exact melody line from "India" being played by McGuinn on his 12-string guitar (his surrogate sitar).

Guitarist Larry Coryell was experimenting with rock chords and sound effects from the time he arrived in New York City (from Seattle) in the Fall of 1965. Working with Chico Hamilton in the latter's Quintet, Larry began experimenting with a more rock-oriented band in the same year who called themselves The Free Spirits. Though they only released one studio album, the band gigged live enough to make a name for themselves--and to let Larry find the sounds and styles he wanted to continue exploring. His playing with both Chico and The Free Spirits got him noticed by adventurous and "inclusionist" jazz vibe player Gary Burton. Larry left his former bands and played with Gary's Quartet with whom he recorded and released four albums in two years, 1967 and 1968, one of which, Duster, is largely considered one of the first, if not the first, true jazz fusion album. Burton had for some time called himself a nondenominational musician. Claiming that he not only liked the music of his age but felt open and comfortable incorporating the sounds, styles, structures and melodies of all musics into his own performances, compositions and recordings.

At the same time, Coryell continued exploring his own ideas in the studio. With the support of disgruntled John Coltrane rhythm section, drummer Elvin Jones and bassist Jimmy Garrison, as well as friend Bob Moses, Larry produced a solo album in 1968 that was released in early 1969 called Lady Coryell (inspired by his new artist wife, Julie Nathanson--his inspiration and collaborator). This album shows definite attempts to merge jazz music with rock sounds and stylings.

In England, jazz, rock, and blues traditions had been flourishing since the 1940. Artists like Sidney Bechet, Ronnie Scott, Chris Barber, Joe Harriott, Kenny Ball, Chris McGregor were busy spreading their sound as well as inspiring, grooming, and even mentoring some of jazz-rock's future stars like Mike Westbrook, Graham Collier, Michael Garrick, Mike Gibbs, John McLaughlin, Dave Holland, and Kenny Wheeler. Bands/musicians like The Yardbirds, John Mayall, Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce, Pink Floyd, The Beatles and Daevid Allen were playing with smoothing out the boundaries between musical genres like the blues, rock, and the "free jazz" movement with electronic and taping effects to incite a burgeoning psychedelic scene. All of these musicians were extremely and profoundly effected by their introduction to the music and live concert performances of Jimi Hendrix. The 1966-68 trio of Baker, Bruce and guitarist Eric Clapton, known as Cream, may have been the most famous and successful of the crossover artists. By the close of the 1960s, Jazz-Rock and Jazz Fusion had found a firm place in the British music scene--especially in the Canterbury Scene.

The San Francisco Bay Area/West Coast psychedelic scene was also legendary for its influences on music as well as pop culture. Without the experimentalist zeitgeist of California's counter-culture that led to events like and Bill Graham's January 14, 1967, "Human Be-in" event in San Francisco's Golden Gate Park or the Monterey International Pop Concert of June of 1967 there might not have been a full-blown "Summer of Love"--which exhibited itself in the form of a tidal wave of "hippie love" psychedelia in the American music scene.

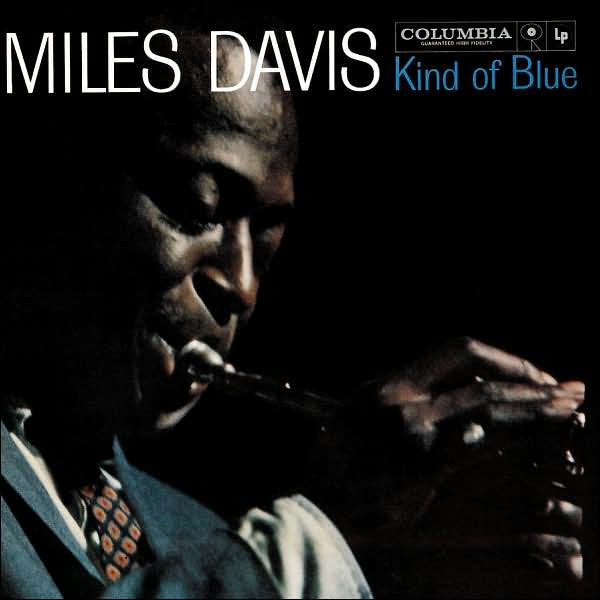

Miles Davis had some early forays "outside" the accepted boundaries of jazz (more accurately, Miles was one of the artists who was always pushing at the boundaries of jazz, taking it into new territory which would then become absorbed as an acceptable part of jazz) with such albums as Round About Midnight, Milestones, and Kind of Blue. It cannot be said, however, that Miles musical shifts were instigated or inspired by spiritual inputs as was the case for so many others. Rather, Miles' shifts occurred through exposure (often social and accidental) to other 'new' musics and other musicians with their new ideas and own personal influences. While all of the band members he used through the years brought strong personalities and their own ideas and growth trajectories, it might be said that Miles served as a catalyst for many musicians in the same way that a chemical reaction is sped along by the addition of some new substance or information. Or perhaps a better interpretation of the results was that the mix of each new band 'concoction' provoked transformative change in all present--even Miles. Whatever the case, the list of musicians who jammed or recorded with Miles through the years might make up half of the roster of the Jazz and Jazz Fusion Hall of Fame. Jazz music--and jazz fusion--were prodded along by Miles and these musicians.

Where was Miles' biggest shift in his evolution to a true jazz-rock fusion? Arguably, it was the 1967 Newport Jazz Festival. He brought with him to the festival his second "great quintet." This band included future fusion pioneers and stars as piano-keyboard player, Herbie Hancock (the five "Mwandishi" albums of 1971-3), saxophonist Wayne Shorter (The Jazz Messengers, WEATHER REPORT), drummer Tony Williams (The TONY WILLIAMS LIFETIME, V.S.O.P.) and bassist RON CARTER (who stuck most closely with his jazz roots). The Quintet had already produced albums like E.S.P., Miles Smiles, Sorcerer, Nefertiti, Miles in the Sky, and Filles de Kilimanjaro as well an album that is often considered their crowning achievement, The Complete Live at the Plugged Nickel 1965.

This had been a relatively stable time in Miles' life--and this is reflected in the music of these albums. While The Miles Davis Quintet was on the evening bill for the final night of the 1967 Newport Jazz Festival, had he been present as an audience member on either of the previous days he might have seen the experimental and proto-fusion work of the likes of Babatunde Olatunji, Gary Burton and The Gary Burton Quartet ("With Larry Coryell"), Albert Ayler, Dizzie Gillespie, John Handy, and Herbie Mann. In 1968 he could have seen the likes of The Don Ellis Orchestra, more of the Gary Burton Quartet (with Larry Coryell), as well as Mongo Santamaria and Hugh Masakela. Also in 1968, Miles married young model-singer Betty Mabry. Betty was the sole reason Miles was introduced to a lot of pop culture stars that had been a part of her own New York social circles--including Jimi Hendrix and Sly Stone. In a curious shift in patterns, Miles brought in new musicians for the February 1969 recording sessions at New York's Columbia Studios--musicians who were busy experimenting with electronic sounds. These included British guitarist John McLaughlin, and a second and third keyboard player in Hungarian keyboard whiz Joe Zawinal and Chick Corea to play with Herbie Hancock. The result was released at the end of July as In a Silent Way.

Though Miles and Betty divorced in 1969, Miles had the occasion to share billing in July at the 1969 Newport Jazz Festival with several of Betty's friends--including Sly Stone. It was this Newport Jazz Festival of 1969 that changed everything--for Miles and for jazz music. Featuring a more-expanded list of musical genres--especially representative of the pop scene--Miles would have had the chance to see the Sun Ra Archestra, John Mayall, James Brown, Sly & the Family Stone, Frank Zappa and the Mothers of Invention, as well as Blood, Sweat and Tears, Jeff Beck Group, Jethro Tull, Steve Marcus, and Alvin Lee and Ten Years After on Friday night's "Evening of Jazz-Rock" and B.B. King and Johnny Winter and Led Zeppelin on the final night. As some observers note, Miles came away from Newport "on fire;" there was Miles before Newport 1969 and then Miles after Newport.

The first studio project after the Newport Jazz Festival came in August--the 10th through the 21st, to be exact. Though In A Silent Way came out later that same July, it had been recorded months before. For these August studio sessions Miles recruited a large ensemble, many of whom had been experimenting with electronic instruments for some time. The Bitches Brew sessions are famous for the presence of a large group of studio musicians--even more expanded than on In A Silent Way. Miles invited long-time collaborators Wayne Shorter on soprano saxophone and Dave Holland on double bass, and then guitarist John McLaughlin and the three keyboard players from the previous album, Joe Zawinal, Chick Corea, and Herbie Hancock. Gone was the powerful drumming of Tony Williams--who had left to from his own power jazz trio with John McLaughlin and organist Larry Young. Instead he used the more subtle, Latin-influenced work of Don Alias, Lenny White, Jack DeJohnette and percussionist Juma Santos (sometimes all at once). Also, a second bass player, Harvey Brooks, was included to provide the contrasting electric bass guitar to Dave Holland's acoustic stand-up. Perhaps the most effective and eerie addition was that of bass clarinetist Bennie Maupin.

On the first day, at Columbia Studio B in New York City, the band of twelve musicians cranked out three songs including the title song, "John McLaughlin," and a new version of Wayne Shorter's "Sanctuary"--the last two minus bassist Harvey Brooks.

- On the next day the same ensemble minus drummer Lenny White gathered to complete the "Miles Runs the Voodoo Down" (14:04 in length on the vinyl album release). On the final day the ensemble was expanded again with the the return of Lenny White and the addition of organist Larry Young as the third and "center" channel's electric pianist in place of Herbie Hancock. The day produced two songs, "Spanish Key" and a cover of Joe Zawinal's "Pharoah's Dance." (All other songs are credited to Miles.)

- Every name mentioned from the recording sessions of these two albums went on to become major players in the Fusion explosion that occurred in the following year or two.

Gary Burton: Duster (1967), Crystal Silence (with Chick Corea) (1973), The New Quartet, Ring (with Eberhard Weber and Pat Metheny) (1974), Dreams So Real, Passengers

The Soft Machine: Third (1970), 5 ("Fifth"), Six, Seven, Softs, Bundles (1975)

National Health: National Health (1978), Of Queues and Cures (1978)

Joni Mitchell: The Hissing of Summer Lawns (1975), Hejira (1976), Don Juan's Reckless Daughter (1977), Mingus (1979)

Eddie Henderson: Realisation (1973), Inside Out (1974)

Stanley Clarke: Children of Forever (1973), Stanley Clarke (1974), Journey to Love (1975), School Days (1976)

Al DiMeola: Land of the Midnight Sun (1976), Elegant Gypsy (1977), Casino (1978), Splendido Hotel (1980)

Freddie Hubbard: Polar A-C (1975), The Love Connection (1978)

SBB: Nowy horyzont (1975), Pamięć (1976), Ze słowem biegnę do ciebie (1977), Slovenian Girls (1978), Memento z banalnym triptykiem (1981)

The list is by no means exhaustive: I'm certain I've left out many, many albums that are deserving of being included; these are but. the albums I know and can vouch for.